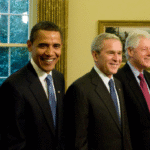

During Barack Obama’s first term as President, many liberals expressed frustration with what they viewed as a lack of strong leadership. Critics pointed to the debt ceiling negotiations of 2011, the weak economy, and stalled progressive reforms as evidence of a “failed presidency.” Yet this criticism reveals a misunderstanding of the true limits of presidential power in the U.S. political system.

Why Liberals Felt Disappointed in Obama

Progressives had high expectations for sweeping reforms, such as:

-

A public option in health care.

-

Tougher financial regulations on Wall Street.

-

A larger economic stimulus following the 2008 financial crisis.

When these goals didn’t materialize, many concluded that Obama was either too weak or too willing to compromise. Even liberal media outlets like The New York Times amplified this criticism.

But this view overlooks a fundamental truth: the President cannot simply dictate policy.

The Reality of How Lawmaking Works

The U.S. government operates under a system of checks and balances, especially during divided government. While the President is the most visible figure in Washington, his powers are limited to three primary areas:

-

Signing or vetoing legislation passed by Congress.

-

Setting the national agenda by prioritizing issues.

-

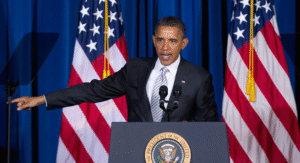

“Going public” — using the media to shape public opinion, a concept highlighted by political scientist Sam Kernell.

In practice, Obama only had full control over the third. The others depended on Congressional cooperation, which was hard to come by in a polarized era.

Congress Was (and Still Is) More Unpopular

Obama’s approval ratings in 2011 fell below the historical average for presidents at that stage in office. However, Congress was far less popular than the President. Surveys showed Americans disapproved of both parties in Congress even more strongly than they disapproved of Obama himself.

This raised an important paradox:

-

Voters recognized Congress as ineffective.

-

Yet many still blamed Obama for not delivering major reforms.

The disconnect lay in public expectations. Many believed the President could achieve sweeping change through sheer willpower. In reality, the Senate filibuster, party divisions, and institutional gridlock prevented Obama from enacting policies that liberals demanded.

Why Presidential Power Is More Limited Than We Think

The modern presidency is powerful but not absolute in its authority. Unlike historical figures such as Lyndon B. Johnson, who wielded immense influence over legislators, Obama faced a far more divided Congress. For instance:

-

A larger stimulus package wasn’t blocked because Obama lacked determination—it was blocked because there weren’t enough votes in Congress.

-

Climate change legislation and expanded healthcare reform stalled not from rhetoric alone, but from institutional barriers and partisan obstruction.

Calls for Obama to simply give a “grown-up talk” to the nation—like some commentators suggested—miss the point. Speeches alone don’t pass laws.

The Bigger Picture

If Americans want a President with more power to enact policies directly, that would require weakening the power of obstruction in Congress, particularly the Senate filibuster. Without structural reform, any President—whether Democrat or Republican—faces the same constraints.

Key Takeaway

Barack Obama was not a “weak leader” simply because he failed to deliver every progressive goal. His presidency highlights the structural limits of executive power in the American system. While leadership and rhetoric matter at the margins, no President can overcome institutional roadblocks alone.

For critics across the political spectrum, the lesson is clear: lasting change requires systemic reform, not just presidential willpower.

+ There are no comments

Add yours